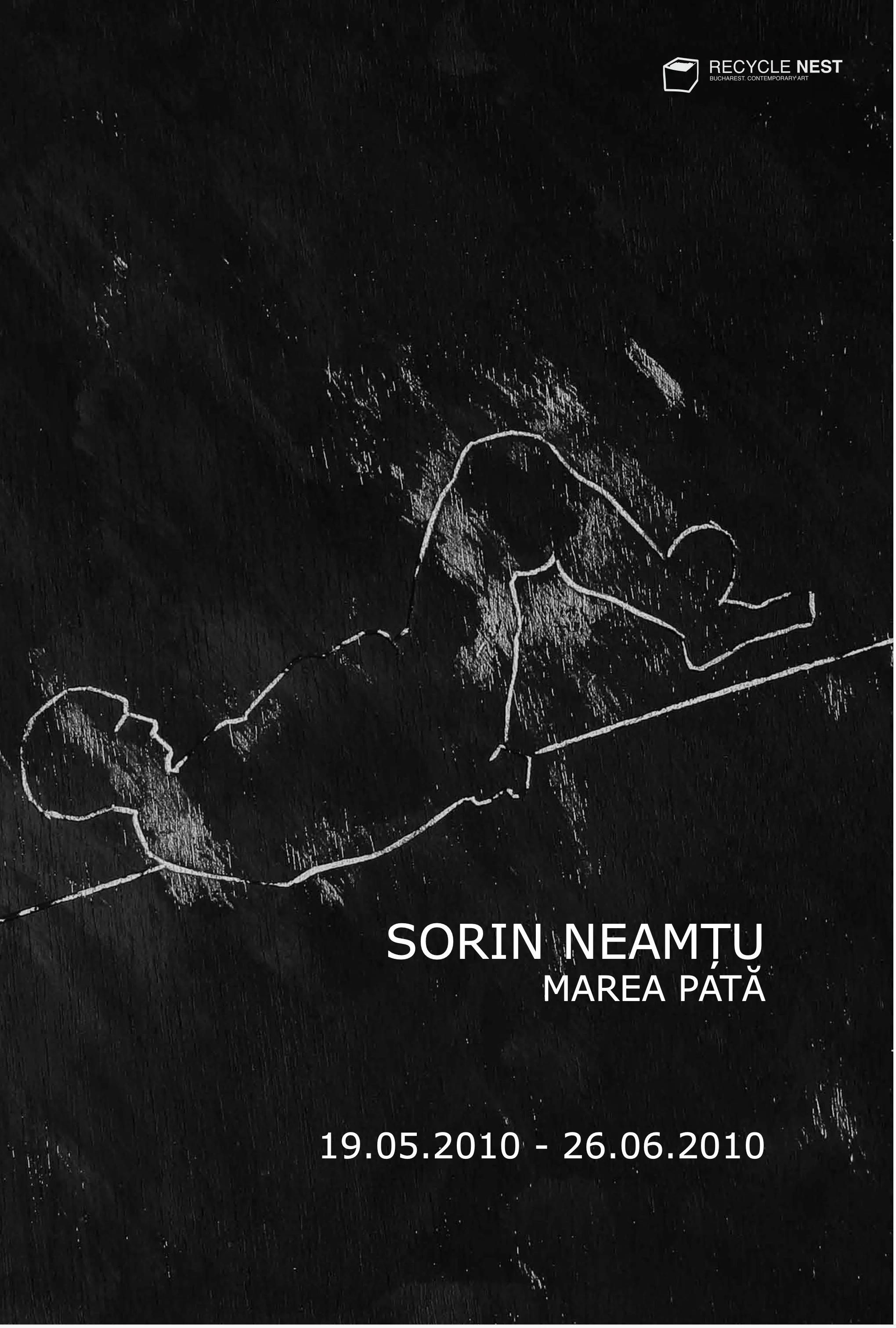

Marea pată (The Great Blot) | Recycle Nest Gallery, Bucharest, 19.05 - 26.06. 2010

-

8 Mai 2010

Actuala expunere de la Recycle Nest prezintă un pictor în criză, gata să riște integritatea propriei producții artistice prin acțiuni menite să-i biciuiască și violeze patternul creativ. În consecință, picturii masive și monolitice pe care o practică în mod curent i se va opune interstițiul; solidității și evidenței i se va juxtapune dubiul; modelului stabil și incoruptibil îi va corespunde, de astă dată, exemplul fragmentar și tranzitoriu.

Ca pictor, am următoarele observații: Cred că e bine să asumăm deranjul crizelor din interiorul picturii chiar dacă ne trădează constituția fixă a echilibrului unora dintre noi. Intuiesc în aceste tensiuni teritoriul fertil al schimbărilor și prilejul întrebărilor. La urma urmei, cei treizeci și trei de ani ai lui Neamțu reprezintă o vârstă care absoarbe impasurile și predispune la revolte personale. Crucea devine sesizantă și pe netitatea peretelui galeriei, printre lucrări.

Neliniștea scrierilor din cartea tiparită acum, fotografiile care întrerup pictura celor două semne masive ale stâlpilor și containerelor, dar și pictura nouă practicată prin tăieturi și unghiuri ascuțite vin să întărească subiectul unei schimbări dorite de Neamțu. Îmi pun întrebarea cât dintre acestea sunt dorite dinadins sau reușesc să întrerupă inoportun discursul despre pictură.

2009. Întâmplarea irepetabilă din curtea cu garaj a lui Sorin Neamțu sugera o expoziție reușită, capabilă să descrie pictorul și lucrările lui. Mâinile mari învârtind pânzele scoase din cămara ce le adăpostea, aerul bătut de acestea, lumina cu umbră și soare, cei câțiva care asistam la spectacol, disconfortul lecturii de aer liber, ș.a., toate comentau o situație necomplicată și bine descrisă a picturii sale. “Marea Pată” nu are aceste atribute. De astă dată se pregătește o expoziție vulnerabilă, a unui pictor cu defecte subtile. “Toate neputințele mele sunt la vedere” aprobă autorul ei, un iubitor al autocricicismului.

Mai trebuie făcută pictură în ziua de astăzi? Ce rost are fotografia în rudenia picturii? Dar cuvântul scris? Să mă descriu prin întrebări îngrijorătoare? Cât de mult mă iubesc pe mine și producția mea artistică? se întreabă Sorin Neamțu.

-

Mi-e un pic jenă că încep cu o referinţă culturală pop, însă mi se pare suficient de nebuloasă şi de semnificativă pentru a deschide un text despre Marea pată a lui Sorin Neamţu.

Aşadar, în clasicul Wild at Heart al lui David Lynch, pe la finalul filmului, după ce Sailor – Nicolas Cage e snopit în bătaie de cîţiva metalişti supăraţi, avem parte de o replică stupefiantă, e adevărat că precedată de una dintre cele mai grotesc simulate scene mistice hollywoodiene: scuturându-şi de praf geaca din piele de şarpe ce rezumă esenţa personalităţii sale, Sailor îşi priveşte agresorii în ochi şi spune: Băieţi, mi-aţi dat o valoroasă lecţie de viaţă.

Dintr-o pedanterie foarte la locul ei într-o discuţie despre Marea pată, fac şi trimiterea exactă către replica de mai sus: daţi căutare pe YouTube Wild at Heart son sahne şi vizionaţi scena de pe la minutul 3, cu subtitrare într-o limbă barbară. Iar acum, să văd dacă pot desluşi pentru cititor istoria brutală a relaţiei mele cu artistul Neamţu. Există în această istorie un eveniment întemeietor, care sper că va fi documentat cum se cuvine la un moment dat: o bătaie pe cinste, o confruntare făţişă într-un - destul de cavaleresc, dar violent - meci de box.

Deocamdată însă, pînă să iasă la iveală proba indubitabilă a acelei lecţii de viaţă pe care sper că ne-o vom fi servit unul altuia, mă mulţumesc să vă împărtăşesc experienţa brutală a rarelor vizite în atelierul aflat în devălmăşia proiectelor şi pe cea nu tocmai confortabilă de asistent şi consumator al unui work in progress aproape exasperant pentru autor: volumul Marea Pată.

Habar n-am cum va arăta proiectul lui Sorin Neamţu după reglajul fin al panotării şi nici cît de îmblînzit va ieşi volumul din pedanta tiparniţă. Ştiu însă că mi-aş dori ca lucrurile să stea, în mare, cam la fel: deloc sau cît mai puţin atenuate. Iar privitorul şi cititorul Marilor pete să se simtă şi ei agresaţi, brutalizaţi şi, nerecunoscînd nici un fel de îndreptăţire pedagogică, stupefiaţi.

Are Neamţu o serie a Capetelor ghem: siluete de copii stinghere, pe al căror chip se citeşte o spaimă recentă (secret de atelier: iniţial, seria se chema Copii dezorientaţi). E ceva fundamental dubios şi crud în chipul unui copil dezorientat. Copiii lui Neamţu par să fi primit, cu cîteva clipe înainte de poză, o corecţie a căror justificare n-o desluşesc. Nu sînt copii luaţi cu binişorul, după cum nici Neamţu nu ştie să ia cu binişorul (cîtă perversitate morală în binişorul ăsta).

Pe vremea cînd era în Celebrul animal, Neamţu mima naivitatea şi miza pe naivitate. Stupoarea pe care încerca s-o provoace era de fapt seducţie. Acum, Neamţu nu vrea să placă, nu caută complici şi intimitate, nu ştie să consoleze. Tutela lui e înverşunată, iar Capetele ghem se rezolvă chinuit, cu Capul în jos. Încîlceala se rezolvă prin contorsiune. Nimic acrobatic însă, doar rîvna aspră şi nespectaculoasă a unui fitness metanoic.

Siluete obscure ale, e de bănuit, adultului deja, care descoperă/ascunde o vină veche, penibilă şi aproape ireală: artistul e acum precum criminalul care-şi suprimă fapta ca pe ceva ce nu aparţine palpabilului.

Nu vreau să cad în biografic sau să mai scrijelesc în fibra morală. Marea Pată nu îngăduie prea multă intimitate consolatoare. Melancolia postúrilor – sau ce-o fi ea: melnclie – e rece: nimic cald. Reveria, atîta cît e îngăduită de melancolia asta, e sumară, firavă şi dezarticulată de momentele de stupoare. Rezolvă ceva Neamţu? Capul în jos rezolvă cu adevărat Capul ghem?Nu-mi prea vine să cred. Poza oblomoviană din câteva lucrări nu e lene înţeleaptă, e sfîrşeală, aproape înfrîngere. Iar Marea pată e şi urma unei împroşcări violente, ca şi băltire ameninţătoare, ascunzând cine ştie ce şerpăraie. Că se va rupe undeva un dig, sau că totul se va evapora, mă aştept să-l văd peste ceva timp pe Sorin Neamţu ridicîndu-se în picioare, scuturîndu-se de praf şi zicînd: Băieţi...

Cătălin Lazurca

-

The current display at Recycle Nest presents a painter in crisis, ready to risk the integrity of his own artistic production through actions meant to lash and violate his creative pattern. Consequently, the massive, monolithic painting he usually practices will be opposed by the interstitial; solidity and evidence will be juxtaposed with doubt; the stable and incorruptible model will correspond, this time, to the fragmentary and transitory example.

As a painter, I have the following observation: it is beneficial to acknowledge the disturbances of crises within painting, even if they betray the fixed constitution of balance for some of us. In these tensions, I foresee fertile ground for change and opportunities for questions. After all, Neamțu’s thirty-three years represent an age that absorbs deadlocks and predisposes one to personal revolts. The Cross becomes noticeable even amid the starkness of the gallery wall.

The restlessness of the book's current printings, the photographs that interrupt the painting of the two massive signs of pillars and containers, and the new painting practiced through cuts and sharp angles all serve to strengthen the subject of a change desired by Neamțu. I ask myself how much of this is intentional or whether it inopportunely interrupts the discourse on painting.

2009. The unrepeatable event in Sorin Neamțu’s garage courtyard suggested a successful exhibition, capable of describing the painter and his works. Large hands turning the canvases taken out of the storeroom that sheltered them, the air beaten by them, the light with shadow and sun, the few of us attending the spectacle, the discomfort of outdoor reading, etc.—all commented on an uncomplicated and well-described situation of his painting. The Great Blot lacks these attributes. This time, a vulnerable exhibition is being prepared—that of a painter with subtle flaws. "All my weaknesses are on display," the author agrees, a lover of self-criticism.

Should painting still be done today? What is the role of photography in its kinship with painting? And the written word? Should I describe myself through a series of worrying questions? How much do I love myself and my artistic production? Sorin Neamțu asks himself.

-

I am a bit embarrassed to start with a pop culture reference, but it seems hazy and significant enough to open a text about Sorin Neamțu’s The Great Blot. In David Lynch’s classic Wild at Heart, near the end of the film—after Sailor (Nicolas Cage) is beaten to a pulp by a few angry metalheads—we are treated to a staggering line, preceded, admittedly, by one of the most grotesquely simulated mystical scenes in Hollywood history. Shaking the dust off the snakeskin jacket that summarizes the essence of his personality, Sailor looks his aggressors in the eye and says, “Boys, you gave me a valuable life lesson.”

Out of a pedantry that is quite appropriate in a discussion about The Great Blot, I will provide the exact reference for that line: search YouTube for "Wild at Heart son sahne" and watch the scene from about the 3-minute mark, with subtitles in a "barbaric" language. And now, let me see if I can unravel for the reader the brutal history of my relationship with the artist. There is a founding event in this history, which will be appropriately documented at some point: a fair beating, a frank confrontation in a chivalrous yet violent boxing match.

For now, however, until the indubitable proof of that "life lesson" (which I hope we served one another) comes to light, I am content to share the brutal experience of rare visits to a studio lost in the chaos of projects, and the not-entirely-comfortable experience of being an assistant and consumer of a work in progress that was almost exasperating for the author: the volume The Great Blot.

I have no idea how Sorin Neamțu’s project will look after the fine-tuning of the hanging, nor how "tamed" the volume will emerge from the pedantic printing press. I do know, however, that I would want things to remain, by and large, the same: not at all, or as little as possible, attenuated. I like the viewer and the reader of these "Great Blots" to feel assaulted, brutalized, and—recognizing no pedagogical justification—stunned.

Neamțu has a series titled Ball-Heads (Capete ghem): silhouettes of awkward children whose faces reveal a recent fear (a studio secret: initially, the series was titled Disoriented Children). There is something fundamentally dubious and cruel in the face of a disoriented child. Neamțu’s children appear to have received, moments before the photo was taken, a correction whose justification they cannot fathom. These are not children handled "with a gentle touch," just as Neamțu himself does not know how to be gentle (how much moral perversity lies in that "gentle touch”).

Back when he was in The Famous Animal, Neamțu mimicked naivety and bet on it. The stupor he tried to provoke was, in fact, seduction. Now, Neamțu does not want to please; he seeks no accomplices or intimacy; he does not know how to console. His tutelage is fierce, and the Ball-Heads are resolved painfully, with their Head-Down. The entanglement is resolved through contortion. Yet there is nothing acrobatic about it—only the harsh, unspectacular zeal of a metanoic fitness.

Obscure silhouettes of what is presumably already the adult, revealing or concealing an old, pathetic, almost unreal guilt: the artist is now like the criminal who suppresses his deed as something that does not belong to the tangible world.

I do not want to fall into the biographical or scratch further into the moral fiber. The Great Blot allows for very little consoling intimacy. The melancholy of the postures—or whatever it may be: melnclie—is cold: nothing warm. Reverie, as much as this melancholy permits it, is summary, frail, and disjointed by moments of stupor. Does Neamțu resolve anything? Does the Head-Down truly resolve the Ball-Head? I find it hard to believe. The Oblomovian pose in several works is not wise laziness; it is exhaustion, almost defeat. And The Great Blot is both the trace of a violent splash and a threatening puddle, hiding who knows what nest of snakes. Whether a dam will break somewhere or everything will evaporate, I expect to see Sorin Neamțu sometime from now, standing up, shaking off the dust, and saying: “Boys...”