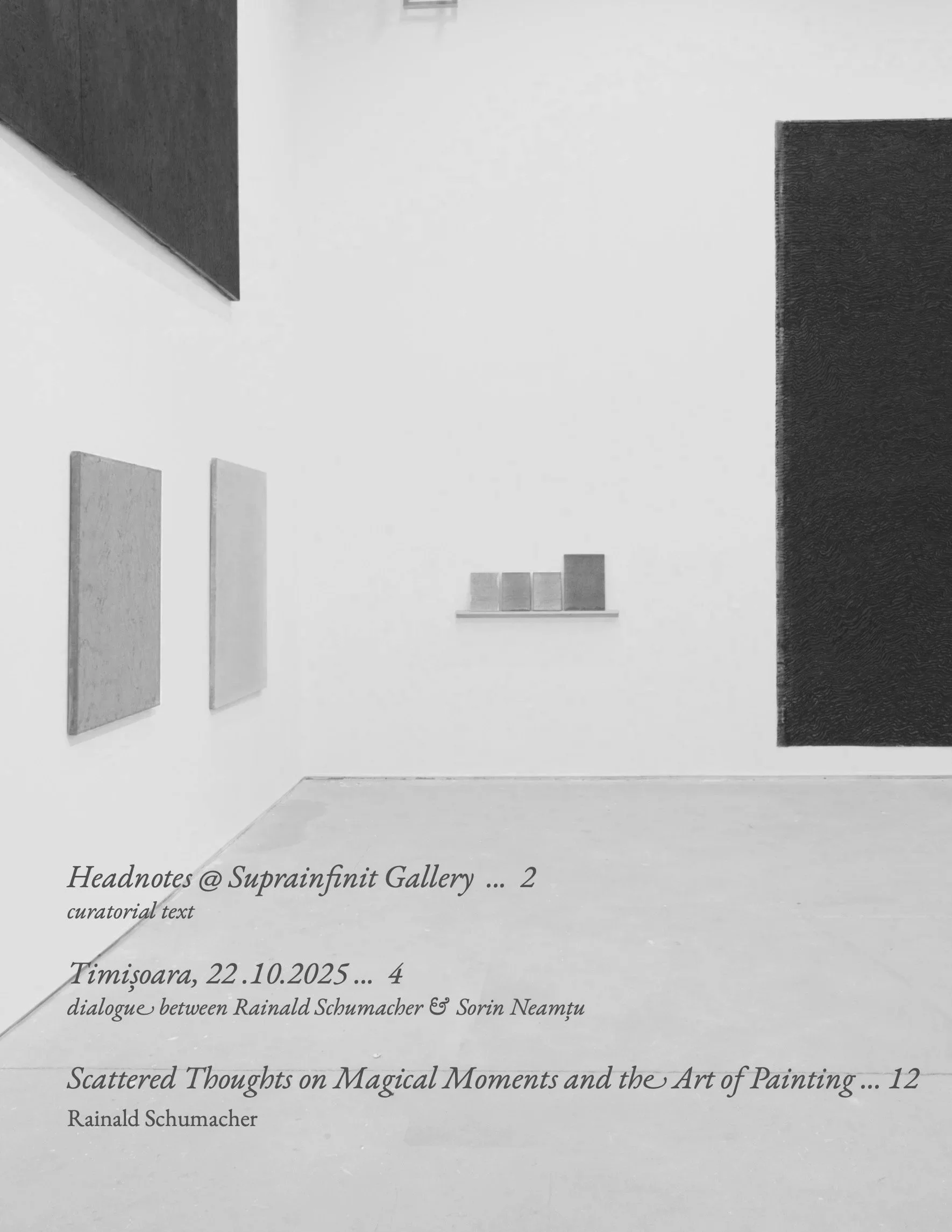

Headnotes, curated by Nathalie Hoyos & Rainald Schumacher | Suprainfinit Gallery, Bucharest | extended until 28 March 2026

-

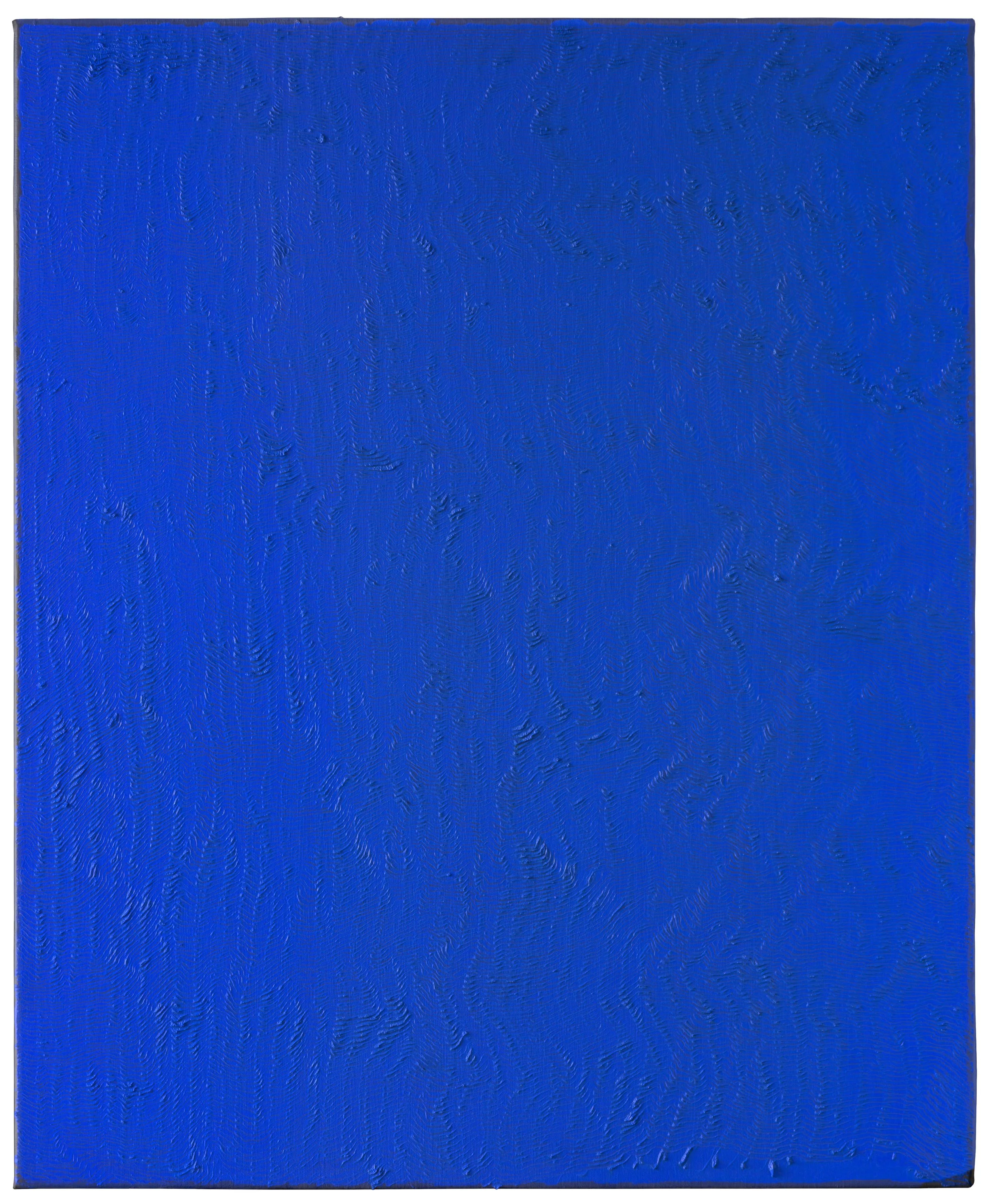

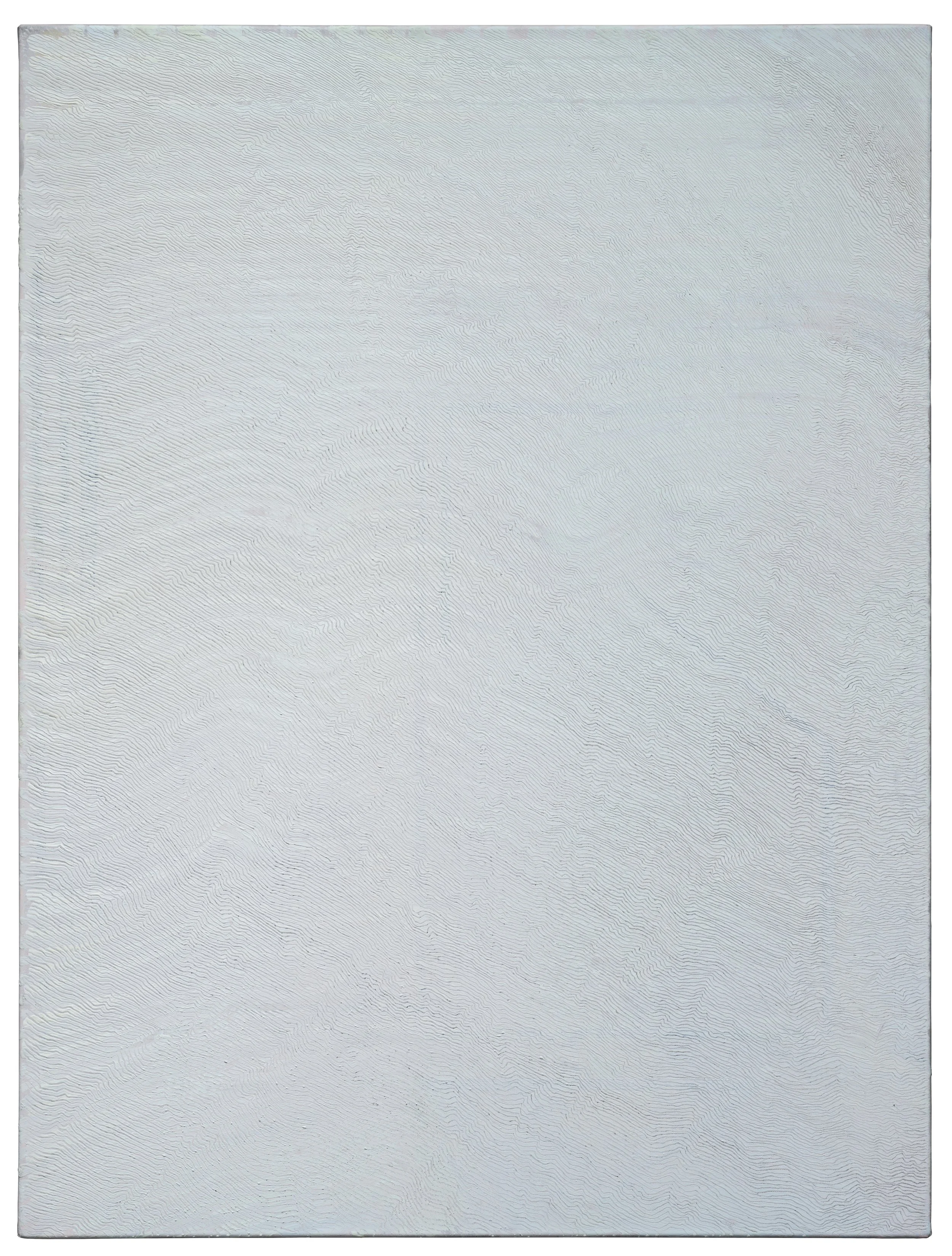

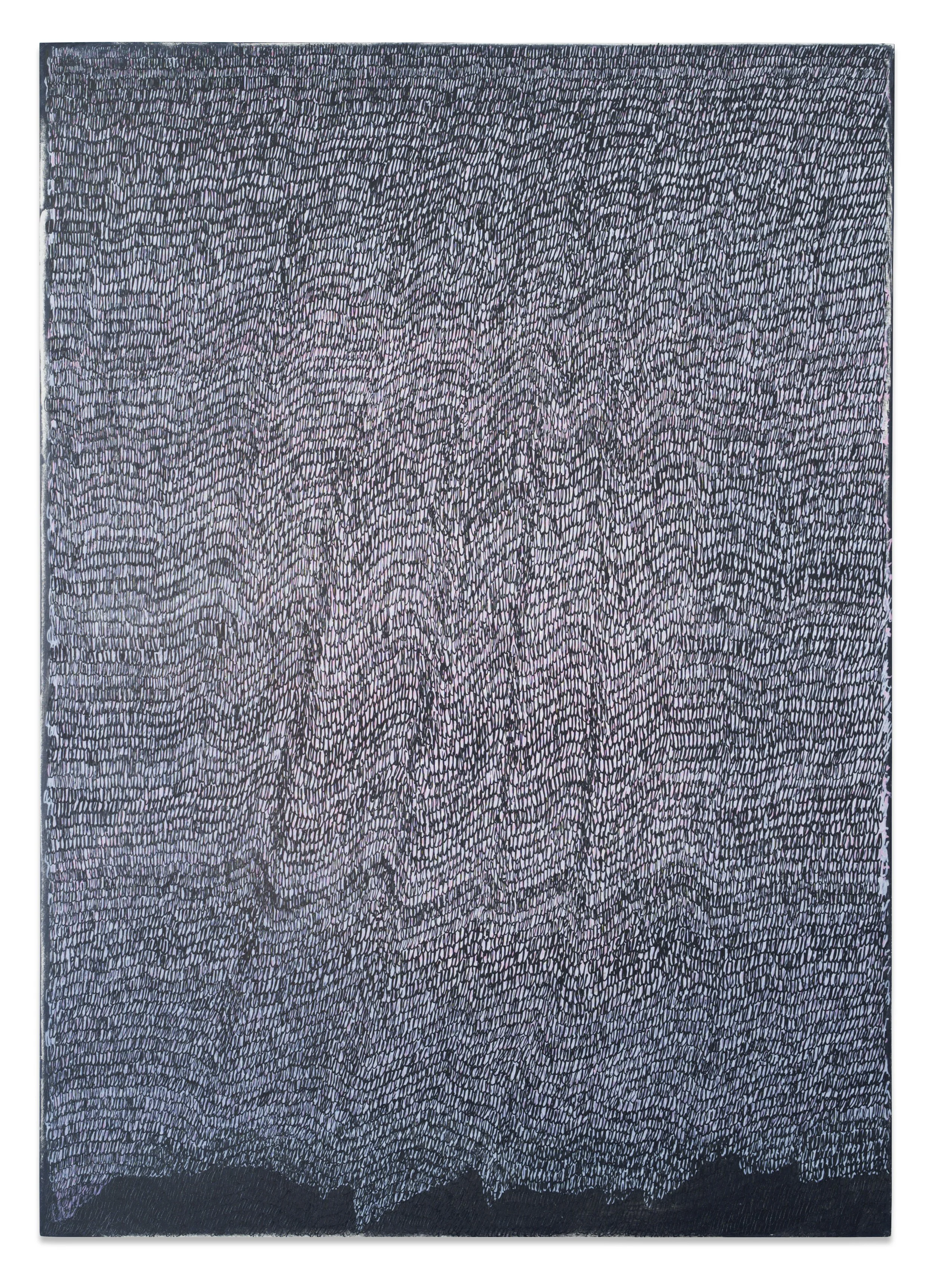

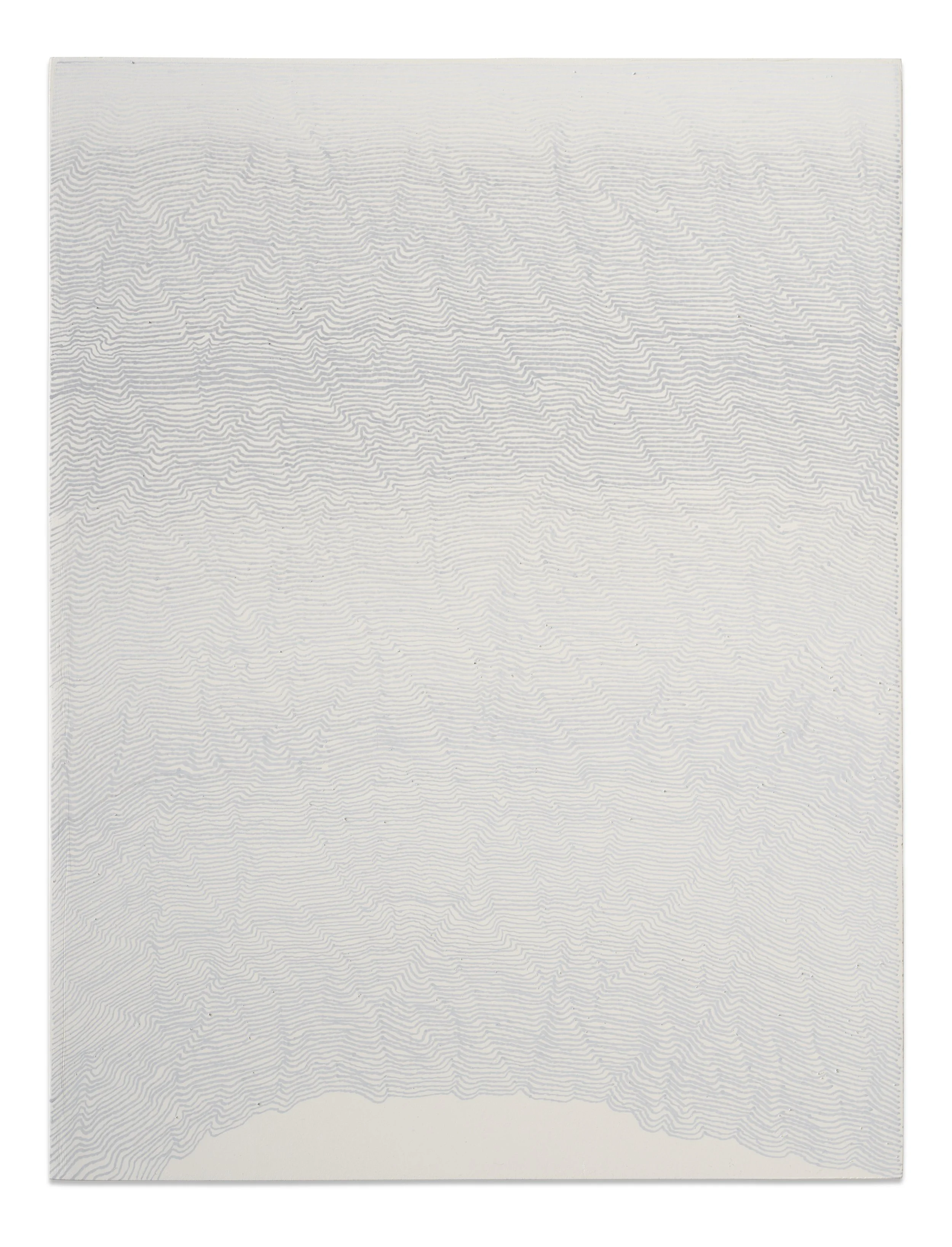

The recent works of Sorin Neamțu, created over the past three years, have emerged from a working process shaped by rules the artist has set for himself. For what would later appear on paper, on a primed wooden surface, on canvas or another material—sometimes painted over an earlier, older work—he chose the line as his point of departure. To this, he added another constraint: once a line had been drawn across the width or length of the surface,—the first one as straight as possible—the next line was to be placed as close as possible to the first, and the next again close to the second, and so on.

This procedure prevents, for Sorin Neamțu, the act of painting from illustrating an idea or concept, or from generating a representation, or an image of a narratively picturesque world. Such outcomes would not align with his understanding of painting. The artist places value on the process itself—the laying down of colour with brush, with quite thick oil sticks, or with the finest of drawing tools, for which he dons a magnifying lens to discern even the smallest distance between lines. For some works, he instead scratches such lines into and out of the colour mass.

To follow the artist’s activity in the studio is one layer through which we may perceive and situate his works within our own world. The result, the finished painting, forms a second layer. Though the painting reveals its individual lines, these converge into a structured surface in which the tremors and minor inaccuracies of each drawn gesture merge into an overall image—a kind of recording of seismic vibrations. Or are they recordings of thought, emotion, of the artist’s psychic state while at work? Are these the Headnotes?

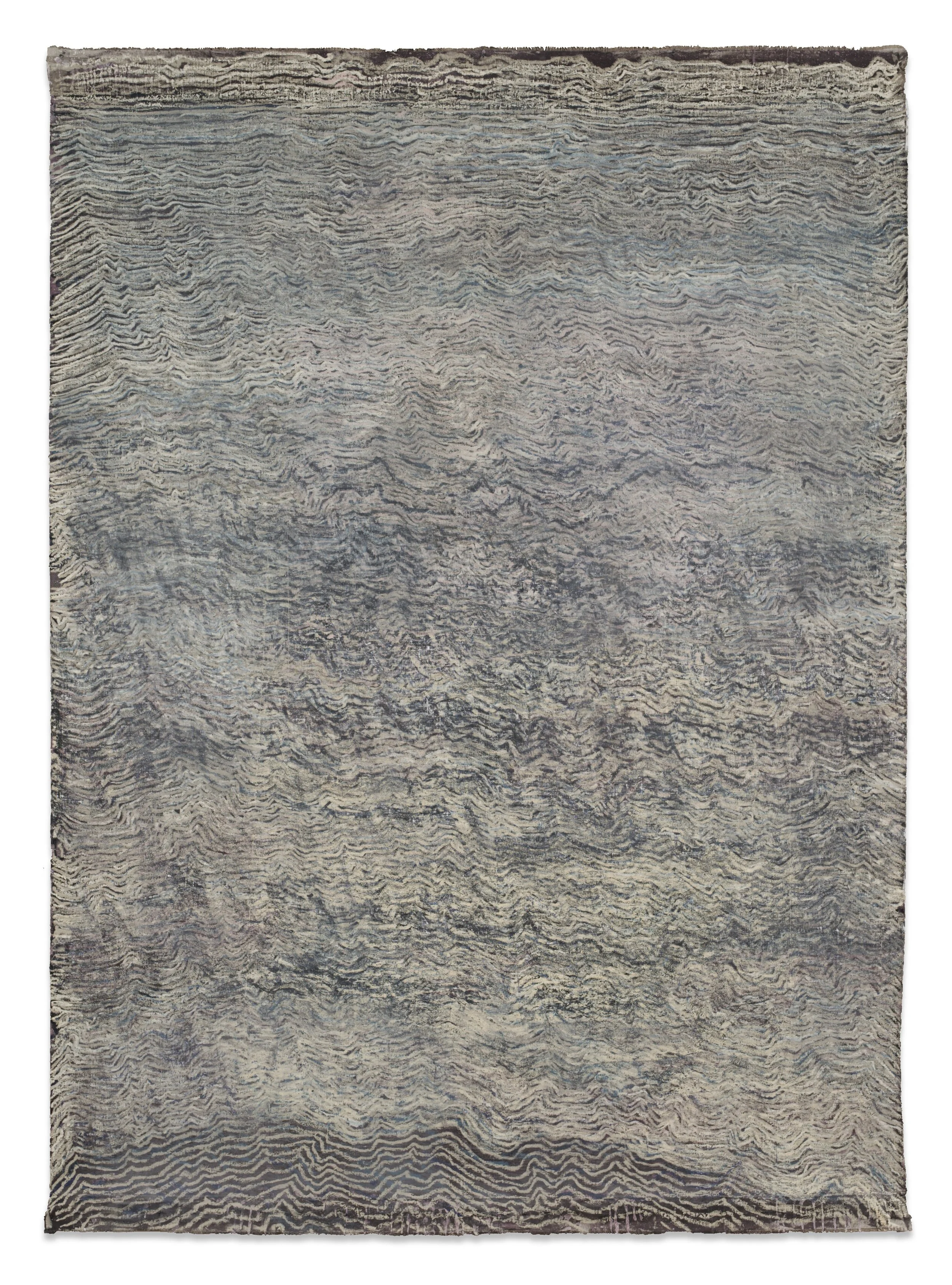

The paintings on display are liberated from preconceived notions, from inner and outer realities that might be depicted, repeated, or rendered in unexpected, surprising, or critical ways. They are open to the associations of the viewer; they are images of a reality of their own. In seeking to sense this reality, the eye looks for what is familiar. Painterly echoes of Claude Monet’s Cathedral of Rouen series (1892—1894) come to mind, with its flickering fields of colour. So too the layered contours of traditional Chinese landscape painting (‘Shan Shui’—‘mountain and water’). The water surfaces of Vija Celmins, or the seascapes of Gerhard Richter, do not seem far away. Even the paintings of the Aboriginal peoples, mapping specific lands, ritual narratives, and mythologies, may serve as reference points.

All these works are the result of a craft-based process and an intellectual negotiation concerning what contemporary art—and painting in particular—can and should be. They are also reflections on what painting may mean to the artist himself, and what significance it might hold for society. This is a mental experiment, a challenge Sorin Neamțu has returned to repeatedly since his work Action with Almost Chair (2012)—a performative act of withdrawal from painting.

The attempt to answer these questions again through painting—these are the Headnotes that hover above the works in this exhibition.

Rainald Schumacher

-

Timișoara | 22.12.2025

Rainald: We are here in the studio of Sorin Neamțu in Timișoara, and together with Nathalie Hoyos, we are preparing this artist’s upcoming exhibition at Suprainfinit in Bucharest, which will open on the 15th of November this year. It’s a rare opportunity to be in the artist’s studio, so we are pleased to have the chance to pose a few questions.

It’s about painting—an old, traditional medium—so we try to approach it with straightforward questions. And the first one is more about the technical side, the process of painting. Sorin, please tell us how you paint.

Sorin: I can tell you how I paint now. It’s a slow process. The paintings I’ve made over the last three years were part of a deliberately slow process. I think it’s essential to make this point: this intentionally slow process was, in a way, in contradiction with my practice until, let’s say, 2022.

I’ve always been a speculative type of person, someone who relates a lot to the environment and to the world, and that was quite visible in my previous practice. Ten years ago, for example, I was painting almost performatively—working simultaneously on large or small canvases with the same paint and the same brush, driven by a gestural intention. I have recently arrived at a very different, almost opposite approach.

Actually, the short version of the story is that one day I found myself here, sitting in the armchair, waiting for inspiration. It was a strange process because it involved laziness and all kinds of projections about what I would eventually paint on that blank canvas, ready to be painted. At some point, this way of being in the studio became unproductive. I told myself I needed to work—whatever it was, I just had to.

My recent works—we are now speaking about painting—are derived from drawings, from a very tedious drawing process. I decided I had to cancel my creativity, in a way, and focus instead on the process, on finding a rhythm, an inner rhythm in working with this kind of practice. From those very tedious works, realised in and with very fine ink pens, on very smooth surfaces, I felt like I had to switch to painting and enter a completely different medium. In drawing, when you work with a single colour—black, red, or white—on a specific support, the relation between the material of the drawing and its surface is quite direct. Painting, by contrast, is much more complex.

What I like about this painting process is that there is always—or at least in a good situation—a kind of chaos, which for me is very important. A painting feels vivid, though I don't know how to measure that, when your brain is in research mode, in a state of experimentation. A good moment is when I’m reacting to what has just happened on the canvas. It’s almost like a dialogue. It’s never about putting an idea on the table or on the canvas and then merely illustrating it.

Rainald: There is a question: what are you painting?

Sorin: Hmm… Who said that every painting is a self-portrait? I think a painter said that, but I cannot remember who. Actually, I refuse to answer this question directly. It’s probably a question floating around in every artist’s studio, but I refuse to take it too seriously. I think there is a similarity with something Richard Serra said in an interview: an artist should never ask “why”, but only “how” and “what” or “what” and “how”. It’s not the same issue, but I feel there is a connection between his statement and this problem of what we are painting, or what I am painting.

If I had to find a common ground for all of my paintings, I would say that it’s a fundamental feeling, a sense of wondering how an image becomes an image—from a white canvas, or from a piece of wood, or some other support. The process of building an image is, for me, the most fascinating thing in the studio. If I’m making abstract paintings—I actually don’t consider them abstract—but that’s another topic, or if I’m making a landscape or a portrait, these terms aren't so important to me.

So I would say: if we can respond to this mystery of how an image becomes an image, or how an object becomes an image…—I don’t want to sound too philosophical here, because I don’t have the tools —, but I think if we can locate this kind of mystery, then the answer to your question is somehow floating somewhere around it.

Rainald: You also mentioned before that you are not illustrating any ideas.

Sorin: No, not at all. Not at all. I think it’s the biggest mistake I ever made, and I’m saying that from my own experience. Maybe Salvador Dalí was thinking differently, I don’t know. Painting should exist on its own terms, stripped of everything we pretend to understand from a Rubens, for example, or from a Caravaggio painting. We recognise the characters there, a biblical scene, a historical event, or something like that. But do we really understand what that painting is? When I say this, I’m thinking of how broader audiences tend to approach paintings through their subject matter.

For example, I’m thinking of Francis Bacon, for instance. He is very famous, but the same experience can also emerge from other artists’ works. I am—as far as I can say— very far from his imagery. I’m not interested in his subjects at all, but I get emotional every time I see his paintings. There is something almost miraculous when you get close to a Francis Bacon painting, and see how he uses the surface, its materiality, the way he prepares the canvas, and so on. For me, the subject doesn’t matter here. I’m not interested in what Bacon wanted to show there, because the painting itself speaks more powerfully than its subject.

Rainald: So I would also like to come back to the point you mentioned about Richard Serra and the two points, “how” and “what”. But I also want to address the third question, which you should never somehow address: “why”. Why?

Sorin: The answer is in my biography. I had the chance to do all sorts of things in my life. I studied computer science for 5 years, and during that time, I also started preparing for art. There is a basic need to express yourself. We all have it. Just look at children, they need to show us what they have made, built, what they have drawn, and so on. For us, as adults, it’s the same, nothing more. We need to express ourselves, maybe in order to look for an inner balance.

I think one should only do art if they can’t do anything else. It’s a good test for a young person who feels drawn to it. If you can hold back from making art, then maybe you should do something else—be a taxi driver, go into business, whatever. But if you can’t refrain from doing art, then you should do it, and then fully accept what it entails, with everything that comes with this choice .

Rainald: You’ve mentioned before that, in some way, maybe all these works by you—or even all art—is somehow related to a kind of self-portrait. And we also have in the exhibition a very early self-portrait that has changed and been adapted. And now we have these new works, which are more or less built up with lines—changing lines, and all the stories between lines—that become a vast kind of network or structure. Visually, it doesn’t have much to do with lines as single things anymore. But how can I also see these works as self-portraits?

Sorin: Of course, it’s obvious that I am using my own image. Generally, my attitude towards myself is pretty critical, or self-critical. I’m rarely satisfied with what I do in the studio. I’m not patting myself on the back when I say that; I’m just rarely confident with the work.

In a very superficial self-projection, I would maybe say that I’m not a narcissistic person. If you ask me about myself, I would still say that. Yet something very strange happens when I am in the studio: sometimes I feel the need to make these self-portraits.

The work you’re referring to is more than a self-portrait. The starting point is a photograph of myself holding a self-portrait painted in oil. In a way, this would be the pinnacle of my narcissism. Some of these works are made through digital print transfer. Ten years ago I've made a mistake on a large painting, about two metres by one and a half. Because of an error in the transfer, I ended up with two heads on the canvas—me, having two heads. I was frightened by that painting, and I covered it up. Now I regret it, because I found a photo of it, and it wasn't so bad; there should have been another solution besides destroying it.

This whole story with the self-portrait goes back ten years or more. Today I no longer treat these images as self-portraits; I’m working with them as containers of a very neutral subject. But if we step back and look at the situation from outside, we see someone, an artist, showing a painting, and there is something meaningful in that gesture. I avoid discussing the whole history of the self-portrait in art. Still, if I recall that painter’s statement I mentioned earlier, there is probably something true in it: every painting, in a way, can be a self-portrait.

Rainald: So it’s also like a mirror for yourself…

Sorin: Interestingly, you mention that, because in 2012, I began working with objects and performances. At that time, I was very dazed and confused, very unsatisfied with what I was doing in my studio as a painter. I was making terrible paintings, and this is not just a heated, subjective retrospective evaluation. I needed to express myself, so I turned to performance. There is a whole story behind them, but it doesn’t matter now. What mattered was that, through performance, in that moment, I felt I could again access an emotional, wondering state that I had been trying to reach in painting. Around that time, I wrote in my notebook that painting is the cruellest mirror I can have.

Rainald: In the exhibition, you have already spoken about some of the older paintings, and about the very critical view you have of some of these older works. Some paintings from this past period are also in the exhibition, but they are overpainted.

Sorin: Most of them.

Rainald: Most of them. It's somehow a mirror of yourself. It's getting overlaid with a newer mirrored image. What is the process...?

Sorin: The process starts with the desperate measures of hiding what I have found, of what I was doing in the past... I tend to overthink things, so I try to simplify my decisions from time to time. I look at a work and ask myself: If tomorrow I were asked to show this painting in an exhibition, would I do it? If the answer is no, I paint over it. Many works end up in that situation, even works that were already exhibited.

I need to paint on them because I’m not starting from a blank sheet of paper or canvas. I’m starting from a point—a very precise point. When I repaint, I’m not necessarily interested in hiding the history of that work. You might still see the materiality of the previous painting, or I might use its last composition as a starting ground. Sometimes I cover everything and then scratch back into it, and all the layers underneath—two, three, sometimes more—come to the surface again. For me, it’s fascinating how the dialogue between these different states of the painting comes into being, how they come together in a meaningful way.

So, I don’t know if it’s about mirroring me, but there is a mirroring—a beautiful mirroring— between these two, three, or four states of the same object, sometimes spanning two years, sometimes twenty.

Rainald: The process itself of working with a line—even with a very free line—and this extended period until the painting might be finished, or at least temporarily finished… it seems to me like a calming, almost meditative kind of practice. Is that how it feels for you, too? Is it something I only sense, or is it something you think about?

Sorin: I think you’re definitely right. But it’s not an intention; it’s a consequence. I didn’t set out to meditate while working. I was trying to avoid laziness. Even now, when I have no idea what to do, I say: “Okay, let’s make a drawing.” I sit with an A4 sheet of paper and stay there for four to six hours, depending on how fine the line is. So yes, there is a meditative consequence.

But I don’t think I’m in some perfect meditative state of mind, because you get tired, you need breaks; after an hour, you need to move, to stretch your back, and so on. Still, there is something there: I don’t get bored drawing those lines because I’m curious what the following five lines, or the following ten or fifteen lines, will do—what they will draw. It’s a drawing where the lines become a surface, if a surface can itself be a drawing. This situation of lines becoming surface is also in that area of wondering. I’m very eager to see it finished and see its outcome.

Rainald: And do you see something in them that relates to visual reality? Do you have associations—from these lines that are growing and developing—to things in the visible world?

Sorin: No, no. I suppose your question is whether I have any reference to visual reality—no, not at all. I’m not looking at the lines in a traditional “abstract” way either. For me, they are a kind of reality in themselves.

Of course, after a while, other people come with their own readings: they say that the lines look like a topographical map, or like a Chinese landscape, as you said yesterday. These reactions gather around the work, help me go further, to understand the gesture of making something, and then having to share it, you don’t really own it anymore. But no, I don’t have any specific references to reality. The references are there, in a way, without me.